AS SEEN IN

Home » Animal Parents: How Species in the Wild Give their Babies the Best Chances

It’s summertime and the wildlife here on the Yorkshire Wolds has turned its attention to the very important job of raising its young. Swallow chicks are clamouring for food. And in the skies above a kestrels carry food to their growing broods.

Despite a lifetime of watching animals in the wild, I still find it fascinating to think how different species have evolved to give their young the very best chance of survival. And although parenting styles in the animal kingdom differ wildly, the methods adopted seem to be in the best interest of each species.

Hares, for instance, leave their leverets alone all day from the moment these youngsters are born, only visiting once a day, at dusk, to feed them. And although this seems harsh, it is a useful strategy for a species that relies on stealth for survival. The principal is that it is harder for predators to spot lone leverets, hidden in long grass or shrubbery, than if they were out with their mother and less able to run for cover.

A hare once hid two leverets in woodland close to my art studio and I noticed she went to extraordinary efforts to keep their location secret. Each night she would take a long, circuitous route to visit them, avoiding owls that might be watching her from above and making sure she didn’t leave a strong scent trail for stoats. I noticed that after suckling, she would drag grass and leaves over her leverets to hide them and to disguise their scent. Read the story here.

Leverets grow up to lead solitary lives and are born ready for this survival style. Despite being just eight centimetres long at birth, they can already walk and their eyes are open.

By contrast, fox vixens are indulgent mothers, doting on their young and guiding them with gentle tolerance. I remember watching one vixen raise five cubs on her own and even after a long day out hunting for their food, she had time to settle amongst them to groom and play with them.

Female weasels and stoats also raise their young alone and are loving, playful parents. Although when it comes to teaching their kits survival skills these tenacious animals take a no-nonsense approach. I once watched a weasel mother take her kits to attack a young rat on their first hunting lesson. When they got there, she stood and left one of the kits to wrestle with this rodent that was double its size. It was a harsh introduction to hunting, but these creatures are one of the UK’s smallest mammals and they need to be tough.

A female stoat has just given birth to kits in my garden, and I’ve been getting glimpses of this first-time mother via hidden cameras. To see the latest, watch my YouTube film here.

Some species, like badgers, bring their broods up in large, extended families. These mammals live together in ancient setts and there is a strict hierarchical order to their clans, with a dominant boar that mates with a dominant sow. The other sows help by babysitting the cubs while their mother goes out to forage.

Birds put in a tremendous amount of effort when raising their young. Reed warblers, for instance are hardworking parents, hunting tirelessly round the clock to find enough food to feed their chicks. This could be the reason cuckoos choose this species as surrogate parents for their own chicks. These tiny birds are among the species most likely to be duped into brooding a cuckoo’s eggs and raising its chick – even though a cuckoo grows to be more than double its size.

In many bird species the males and females bring up their broods together, displaying a healthy equality between the sexes. Among these are kingfishers. The male shares the incubation of eggs and brooding of hatchlings by taking it in turns with the female. I once watched a pair of kingfishers inside their nest and the male took his role in helping to brood the chicks very seriously. If anything, he was the more steadfast parent.

Parents in the wild face tough challenges and those that exercise caution can give their young a good chance of survival. Last year a female kestrel living in my garden fought marauding jackdaws and tawny owls to keep her chicks safe. Sadly, she lost two eggs to their raids, but she bravely remained at the nest and went on to raise five healthy chicks. Click to read her story.

Great crested grebes are sweet to watch with their young. They build floating nests to reduce the chances of predators reaching them from the shoreline and will cover their eggs with twigs and leaves if they leave them. Once their chicks hatch the male and female take a chick each and carry them on their backs and later, once the chicks reach about five weeks, each parent will take sole care of one chick.

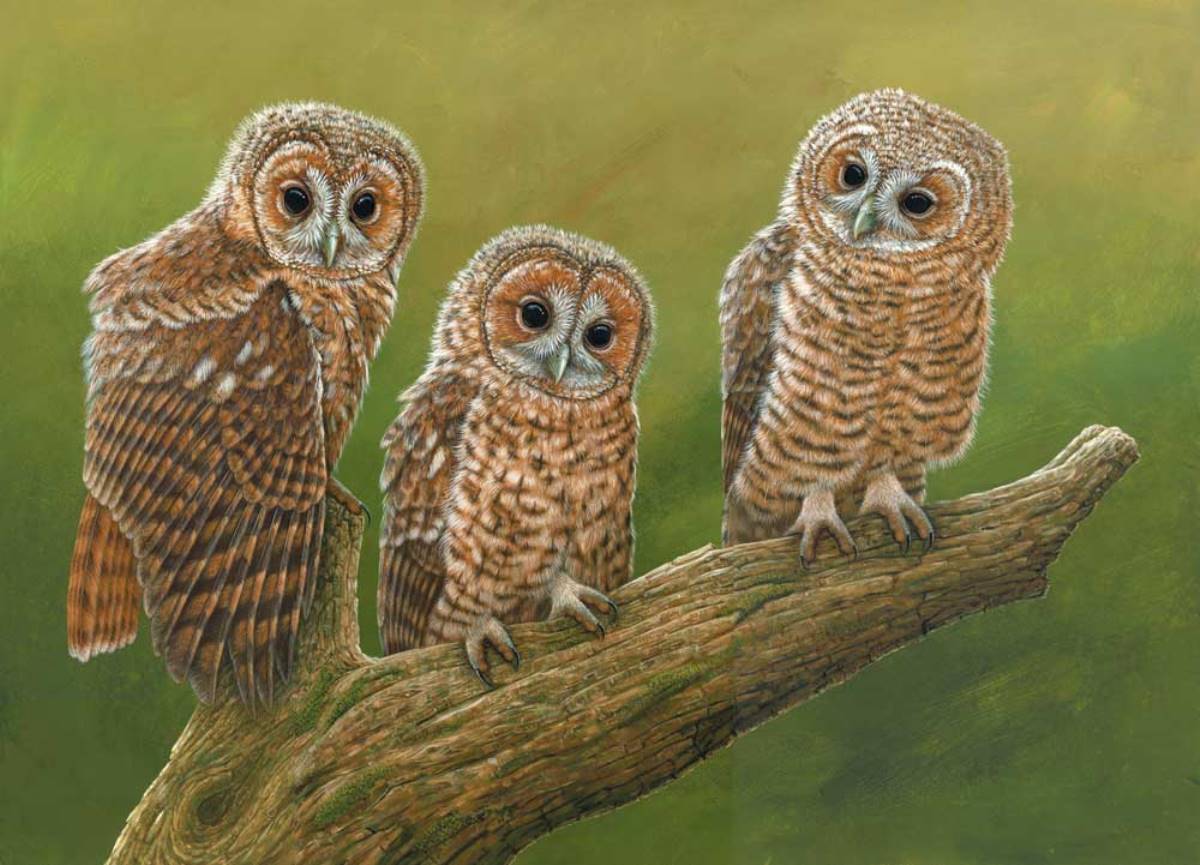

But amongst the most devoted bird parents I have watched are the tawny owls that live in my garden. It’s always endearing to see these birds pay meticulous attention to each chick at feeding times. Every year, once the fledglings have learned to fly, their parents bring them to my bird table to tuck into the treats I leave out for them.

I’ve discovered that these owls’ nurturing instinct is so ingrained that they will even raise injured or orphaned chicks and I regularly place owlets from a wildlife rehabilitation unit into their nest. I use the same technique with barn owls. Read more about the process here.

In autumn, however, as soon as the tawny owlets become teenagers their hitherto loving parents turn on them and chase them out of their territories. At this time, you can hear the parent birds screeching at their young to shoo them away. The strategy can seem a little cruel, but these young need to be off to establish their own territory and start looking for a mate for the following breeding season.

A tawny owl pair living nearby are currently caring for two chicks. You can watch them on my Ash Wood Livestream on YouTube

Sign up to my newsletter for updates on news, wildlife sightings, products and more directly to your inbox

AS SEEN IN

THE ROBERT FULLER GALLERY

FOTHERDALE FARM

THIXENDALE, MALTON

YO17 9LS

UNITED KINGDOM

TEL: +44 (0) 1759 368355

EMAIL: mail@robertefuller.com